Last year I went to the Edinburgh fringe with my show, Static, and lots of things happened simultaneously. I lost my passport on the first day, (I was due to fly to New York just a few weeks later), didn’t know where my accommodation was, and I had a show that depended on a lot of mime and movement and moments of silence, that was put in the corner of a noisy bar. I became very philosophical while I was there, but by the end of the run I was questioning everything and I was ready to consider giving up on spoken word. The usual fringe madness, then.

Last year was a learning experience. I went in softly with Static, an autobiographical piece which I’m still proud of. Indeed I performed the show one last time earlier this year. But on the whole the experience had been a negative one, and I wrote about it in a blog.

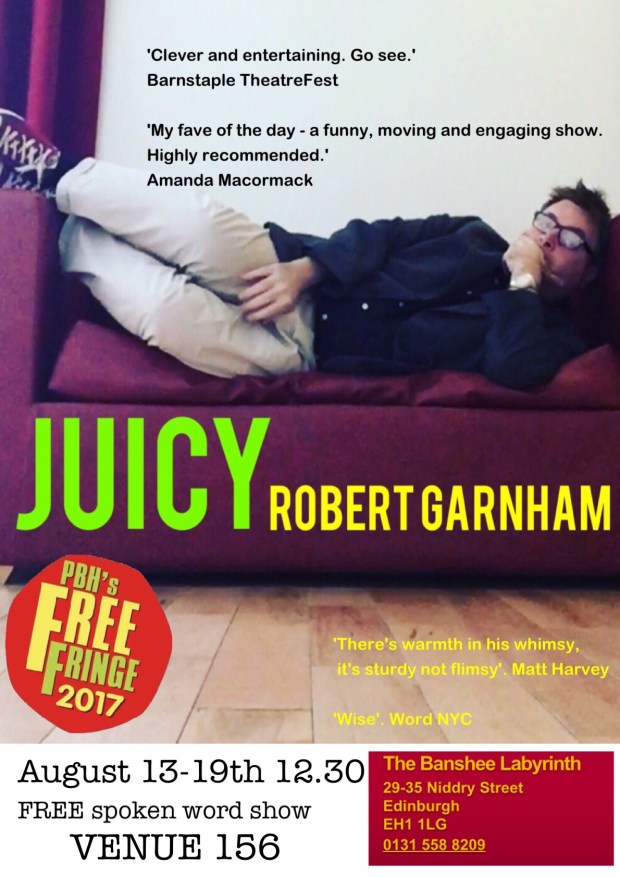

This year, I feel completely different. I have a brand new show, Juicy, which is a completely different beast. Rather than set out with a story and an idea, I just opened up my mind and threw everything at it. The result is a show which has the potential to be different every day, with different poems and different linking material. It’s adaptable, loud and doesn’t rely so much on props and long quiet set pieces. It’s also, I hope, very funny.

But the other thing that’s different this year is that I know more. I know exactly where my accommodation is, I know how it works, I have the travel all sorted out, and I’m pretty sure that I’m not going to lose my passport. The other difference is that my venue is more suited to the kind of show I’ve written, and I’m really looking forward to performing at Banshees Labyrinth every day. Last year, I didn’t know what my venue was like until I arrived, late, breathless, straight off the plane. This year, I know everything about the venue, and I shall be there a day before.

A lot of people helped me over he last year get the new show together, too. At the end of the fringe last year I had a breakfast meeting with one of the top fringe performers, who was good enough to impart all of his wisdom, which I have used to make this show. In particular he told me the importance of music, and this is where my long time colleague Bryce Dumont comes in. He’s helped create a soundscape for me to perform against, and made me familiar with the technology to do this. There has also been support from Melanie Branton, Jackie Juno, Margoh Channing and the mysterious fringe performer, all of whom have offered advice and their own voices for the soundscape of the show.

But the biggest difference this year is that I will know more people there. More friends than ever will be up there with their shows and I aim to see all of them, perhaps several times!

So I’m looking forward to Edinburgh this year!

Tag Archives: funny

On new material

So here I am in Exeter, and I’m early for a gig at the Phoenix Arts Centre, and I’m sitting outside with a Coca Cola while going through my set and practising everything in my head. The event is Taking the Mic, and I’ve been coming here for seven years or so. When I first started coming, Liv Torc was the host, and I was crap. Things have improved since, to the extent that i feel comfortable enough to try out new material at this monthly event.

But I’ve been spoiled, over the years, by good audiences. I’ve had fantastic audiences at different ends of the country, and there have been nights where the audience was so good that I just could not get to sleep afterwards, pumped up and enthused. The downside of this is that I have now become very choosy when preparing for monthly gigs where people have seen me countless times before.

I write a lot and I try to write new material every day. It varies in quality, of course. And the pressure to come up with a good set, and good material at nights such as this, is almost all-consuming. The memory of all those wonderful gigs means that I’m eager to maintain the quality, and feed off of the audience reaction. And if it doesn’t work, or if it doesn’t feel right, then that can be quite depressing indeed.

As a result of this ruthlessness I now have countless poems and pieces which have never made the grade. They sit in my poetry book and I just know that some of them will never get performed. Some of them have been worked over several times, such as the one I’ve been prodding today about a doomed relationship, or the one about having a sofa phobia, which I’ve been working on, on and off, for about six years. I have no idea what I’m going to do with these poems.

I know I should take a risk. I know I should do some of the material that I’m not totally at ease with, the audience will show me whether I should continue hiding such works away, but a part of me doesn’t want to take risks. So as I sit here underneath an umbrella in the rain at the arts centre, I’m going through the set again, just making sure that I’m totally at ease with it. I spent last night rehearsing the new poem and I’m pretty sure it’s ready to roll. But there’s only one way to find out. I shall know the answer in a couple of hours time!

On having a ‘costume’ when performing

I’m a spoken word artist. I’m a performance poet. But right at this moment, as I write this, I’m just Robert Garnham. And the reason I’m just Robert Garnham at the moment is that I’m not wearing my performance clothes. I’m not in my uniform, I’m not in my costume.

When I first started performing I made a conscious effort to wear a kind of uniform for the purposes of standing on stage being whimsical. I have no idea why. I should really have taken the time to create a character, perhaps give myself a different name while on stage, too. But it’s too late now. I’m still Robert Garnham whether I’m on stage or not.

I thought that every spoken word artist had a uniform, a certain look to which they adhered. And perhaps they do, but it seems that my self-imposed uniform is more blatant than most. Every gig now begins with he ceremony of putting on the shirt, tie, jacket, chinos, converse all stars and glasses, then spiking up the old Barnet. And then I travel out to wherever the gig might be.

These are not my everyday clothes. I’m much more casual in ‘real life’, and I’m starting to wish I’d left room for a bit more flexibility when performing. This weekend, for example, I’m at a festival with two performance slots, and it’s going to be outdoors and hot, and yet I feel obliged to wear the usual uniform. The young, trendier poets will be in tshirts and shorts and they’ll quickly jump from non performance to performance with nary a blink of the eye. It takes me about fifteen minutes to get into character as Robert Garnham, Poet.

So. Would it make any difference if I didn’t dress up? Probably not. The word I’m looking for here is authenticity. I’ve seen so many wonderful poets wearing their everyday clothes, being absolutely marvellous at the Mic, an impression heightened by the authenticity of their words and their look. They don’t need to pretend to be someone else.

Which leads me to wonder if everything I’ve done has lacked authenticity because it’s been done from the perspective of an invented persona. Possibly. But as a performance artist, I’ve always attached a lot of importance to the visual as well as the audible. Or perhaps I’m at my most authentic when I’m wearing my performance clothes, and that I’d be strangely inauthentic if I were to start slowing around in what I wear on a normal day. Tshirt, shorts, hoodie, hair all over the place, different glasses. Or maybe still, those who like my work – Robheads, as I call them – wouldn’t accept anything delivered without a certain touch of aesthetic effort.

Or maybe none of this is particularly important at all.

So I’m doing this music festival tomorrow, and you know what? I’m just going to wear something sensible.

Fun at the Barnstaple TheatreFest Fringe

It’s been a couple of years since I was last at the Barnstaple Fringe and I’d always had good memories of it, in particular it’s manageable nature and the camaraderie of the other performers. Coming back this year, I can see that it has grown, and this just adds to its excitement and the variety of shows on offer.

This is my first time here with my own show. I don’t mind admitting that the whole process has been nerve wracking and I was incredibly jittery on the train here the other day, that crazy single line track between Exeter and Barnstaple which seems more like a throwback to the 1950s. This is the first show that I’ve invested a lot in, from rehearsing almost every night to having friends and professionals help out with voice, music and movement. Yet I still had no idea how it would go.

The technicians and the people running the fringe have been very helpful indeed and my mind was put to rest after the technical rehearsal in which it appeared that the technology I was using actually worked! Indeed, the technicians were also pleased because they said that i was, and I quote, ‘low maintenance ‘.

And then the fringe craziness kicks in, the familiar faces you see around town and at other gigs, performers and friends from the local and national circuit all coming together in this small town, this Devonian Edinburgh. And my shows had an audience! Last nights was a classic, for example. On the spur of the moment the technicians suggested using the smoke machine, which certainly added a layer of mystique to the performance and perhaps further adding to the ridiculousness of it.

Bizarrely, the show was reviewed and the reviewer praised my dancing!

Last night I stayed in a venue. By which I mean, Bryony Chave Cox had been performing a production in a hotel room, which she then hired out to me for the night. It was certainly a very strange sensation, having an audience in your hotel room and having to wait for them to leave before getting a good night’s sleep.

So I’ve got one more show to do, and I’m going to try and get out and see as much as possible. I’d really like to thank the organisers of this whole festival, it’s been homely and artistic and everything that a fringe should be. I really hope they let me come back again next year!

What is Juicy? An interview with Robert Garnham

What’s the theme of your show?: Juicy is a scatalogical mishmash of comedy poetry, spoken word shenanigans, serious and deep explorations of loneliness, LGBT rights, songs and a comedy monologue about lust at an airport departure lounge. I suppose if it has a theme, then that would be finding love. Different characters throughout the show find love, or dream of finding love.

What’s new or unique about the show?: Juicy is a free form entity, different every night, with no definitive order. It’s upbeat and funny one moment, contemplative the next. It looks at some serious issues, too, behind the fun and the hilarity, such as gay rights in places such as Uganda and Russia, loneliness, isolation, longing.

How did the show come into being?: the show just kind of evolved outwards from several different places simultaneously, somehow, in a kind of spoken word osmosis, meeting in the middle. It started with a few ideas, which were improvised, then these ideas led to other ideas.

Describe one of your rehearsals.: The show is in three parts so rehearsals were conducted in fifteen minute sessions in a shed at the back of my parents garage in Brixham, Devon. This is real home grown stuff! There’s a big mirror along one wall where I can watch myself practising. I play around a lot with word order and tone and movement and hey presto, the show started to come into being.

How is the show developing?: One of the important aspects was the adoption of music. I worked with some talented musicians and sound artists, which really helps with the tone and the delivery. And then I was privileged enough to work with Margoh Channing, one of the funniest cabaret drag artists of the New York scene, and she recorded some words for the end. I just knew that the end would have to fit in with her words!

How has the writer been involved?: The writer has been involved since the start. I’m the writer. I’ve been there for every rehearsal.

How have you experimented?: As I say, the music was the key to the show. I’ve performed all over the UK and New York for years, but never used music before. Most of my experimentations were actually with the technology necessary to get the music backing just right. I’ve also never done a long monologue before, so this was kind of scary. I was influenced by another New York friend of mine, the storyteller Dandy Darkly.

Where do your ideas come from?: I wish I knew! They just seem to arrive. Like being hit in the face by a kipper. You can be in a sauna or swimming pool or on a bus about to get off and suddenly, oh yeah! A badger that wants to be in EastEnders!

How do your challenge yourself or yourselves?: I watch other performers and see how they do it. And then I try to be as good as them. I’m really influenced by cabaret artists, even though I’m a spoken word artist. The sense of fun and naughtiness is irresistible.

What are your future plans for the show ?: Juicy will be going to GlasDenbury Festival near Newton Abbot, the Guildford Fringe, and then the Edinburgh Fringe, where I’ll be at Banshees Lanyrinth.

What are your favourite shows, and why?: Margoh Channing’s Tipsy, for the humour and the pathos. Dandy Darkly’s Myth Mouth. Paul Cree, Ken Do. All these people invent characters and invest them with humour, and take you to new places almost effortlessly. I’ve seen them all at various fringes. Also Melanie Branton’s new Edinburgh Show, she’s such a good writer and performer.

Show dates, times and booking info: 29 June at 5pm, 1st June at 650pm, 2nd June at 330pm, all at the Golden Lion in Barnstaple, tickets available on the Barnstaple TheatreFest website.

Then the Keep pub, 9 July at 730pm, Guildford Free Fringe, tickets available, again, from their website.

And finally at Banshees Labyritnth, every day at 1230pm, 13th to the 19th August, at the Edinburgh Fringe.

My writing life.

I started my writing career in 1981. I was seven. In a style which I have later adopted in my poetry, my first novel didn’t have a title, it just had a giant R on the cover, which stood for Robert. I can’t remember much about if except that the villain was an entity known only as the Blue Moo. The Blue Moo was what I used to call my sister, because she wore a blue coat. Which is kind of cruel, seeing as though she was only five at the time.

I would write at school during playtime, whenever it was raining. It rained a lot, I remember, when I was a kid. I’d always get excited about rainy days because it meant that I could write. I still get excited shout rainy days, even now.

By 1984 I was at middle school and I used to fill notebooks with stories. I was encouraged to do this by my teacher, Mr Shaw, who would then let me read my stories out in class. The first of these was called Bully Bulldog’s Ship, and for reasons which I’m still not sure, all of the characters were dogs. And secret agents. The cover for Billy Bulldog’s Ship shows explosions and a radar screen and has he tag line, ‘Featuring car chases, underwater bases, kings and prime ministers and that sort of thing’. It was rubbish.

By 1986 I was still at middle school, but now I’d progressed to writing about humans. I wrote a whole series of short novels about a skier, called William Board, and his friend Ed Butf, and how they would get into all kinds of adventures during and after skiing tournaments. I have no idea why I picked skiing tournaments, but I did watch an awful lot of Ski Sunday back in the day.

In 1988 my grandparents gave me a typewriter, which I still use now whenever I’m Poet In Residence anywhere. By now William had left the skiing circuit and was a policeman in a small Surrey village called Englemede. I’d type up these stories and inject as much humour as possible, because this would make my English teacher, Mr Smith, laugh as he read them. This was probably a big moment in my adoption of comedy. The stories were still rubbish, but my grammar and spelling had improved.

By the time I got to sixth form I was still plugging away, and remarkably, William Board was still the focus of the stories, his ineptitude as a policeman and his promotion to detective providing much mirth. My magnum opus of this time was Impending Headache, set at a sixth form college in Surrey much like the one I attended. And in between chapters I’d write over the top comedic poetry.

By 1992 I had my first job and, amazingly, William Board was still my main focus. By now his detective work would take him to a supermarket in Surrey, round about the time that I worked at a supermarket in Surrey, in a novel called Bar Code Blues.

In 1994 I got a job in a village shop in the suburb of Englefield Green, and I wrote a new novel with a new main character, the trainee guardian angel Genre Philips. The novel was called Englefield Green Blues, and like Impending Headache, it would be influential on my writing career in that I’d re-use chapters and stories to form the novel I’ve been working on this year.

At this stage, I’d started sending novels off to publishers and agents, and one or two were very supportive but would ultimately say no.

By now I’d dabbled in comedy poetry, filling up notebooks with poems written with a pen I’d been using since sixth form. I’d stay at my grandmothers house in the hot summer, she lived on a hill overlooking the whole of London from the airport to Canary Wharf, and I’d listen to the jazz stations and just write whatever I felt like. This would form the basis of my one man show, Static, in 2016.

In 1995 my Grandfather passed away. I went to see the pathologist and watched as he signed the death certificate with a cartridge pen, and that afternoon I went out and bought one for myself. Amazingly, this is the same pen I use today for anything creative, and it has written every poem, short story, novel and play since 1995.

In 1996 I moved to Devon. By now I’d discovered Kafka, Camus, Beckett, and my writing became dense, impenetrable. I used my own system of punctuation which made even the reading of it impossible, and to further add to the misery, my novels had numbers instead of names. RD05, RD06, RD07, and so on. I’d send these off to publishers and I could never understand why they’d come right back.

I joined a band of local amateur actors and I would write short sketches and funny monologues for them, we’d rehearse and make cassettes, but never got anywhere near the stage. One of my monologues was about a rocket scientist who’d fallen in love with his rocket. Not phallic at all.

I came out in 2000. I didn’t write much at all for a while. I was busy with other things.

By now I had a job, and I’d studied a-levels, undergraduate and postgraduate at night school, so I didn’t have much time for writing. For a laugh, I got a part in a professional play, and while it meant I would never act again, (oh, it was so traumatic!), it led me to write a play called Fuselage. Amazingly, it won a playwriting competition at the Northcott Theatre. I remember getting off the train in Exeter thinking, wow, it’s my writing that has got me here. This all happened in 2008.

In 2009 I discovered performance poetry, accidentally, and kind of got in to that. Around the same time I wrote a short novel called Reception, based on an ill fated trip I took to Tokyo, but by now my main focus was performance poetry and spoken word, shows and comedy one liners. In 2010 I had my first paid gig, at an Apples and Snakes event in London, and amazingly, this was the first time I made any money from my writing since I was 8!

So that brings me up to date, more or less. I now write every day, still with the same pen, and I still use the same typewriter every now and then, though mostly for performance. And I’ve kept a diary, every day writing something about the previous day, which I’ve kept up since 1985 uninterrupted. It’s only taken 37 years to find the one thing I’m halfway decent at!

On memorising.

So lately I’ve been trying to memorise my new Edinburgh show, Juicy. This would be quite an undertaking for me, as I’ve never successfully memorised anything I’ve ever written, and to be jones I probably won’t manage it. I can memorise whole Bob Dylan songs, all fourteen minutes of Desire, but I’m quite hopeless at anything I myself have written.

I did a scratch performance of Juicy at the Bike ashes Theatre in May. It was a daunting experience because I was surrounded by theatrical types, and to be honest I think they were looking at what I was doing more in the context of a theatrical piece than a set of poems. The feedback afterwards unanimously suggested that I should learn the whole thing, because this is what theatre is. Some of the feedback suggested I move around more. Which was quite funny on two counts, firstly because some of the feedback also said how nice it was to see someone who doesn’t move sound all the time, and also because the director I used for my last show told me to stand dead straight for the whole hour. And he was a theatrical director.

So I’ve set to work trying to learn Juicy, and after two months I’ve managed to learn six pages of it. Out of thirty. Now this may not seem like much, but for me, this is a small triumph. I’ve never managed to learn anything before, so six pages of Juicy is the ultimate achievement.

Last week I went to a gig in Totnes and I spoke to a fellow performer who I have lots of respect for. I told her about learning my show and she replied, ‘Why?’

And that got me thinking, why indeed? Ok, so if you’ve learned your lines you can move around more and have a deeper connection with the audience. But on the other hand I’ve always performed with a book, and it is a part of my whole repertoire. I look up from the book, glare at the audience, look at them all in turn. Which should be quite easy at the Edinburgh Fringe. In fact, I know the words, I just can never remember in which order the verses fall.

Make no mistake, it’s good to learn poetry and adds to the performance. And the fact that I’ve memorised six pages of the show means that now I can apply this to the three minute poems, and hopefully grow my performance. But I think I shall just relax on the memorising at the moment and concentrate just on the performance. That’s the main thing. It’s performance poetry, after all!

Ant – A solemn investigation

It has been apparent for some time that a solemn investigation were needed into the effects, physical and psychological, of an ant crawling on someone’s hat. Seeing it as upon myself, (the theme, not the ant), I set out, in a somewhat grave manner, and yet bravely, into such an investigation.

The manner this investigation took soon revealed itself to be poetical in nature, and within a couple of hours I had completed a poem based on the theme of having an ant crawl on someone’s hat. Yet this did not fully satisfy me, and a further poem was written.

At this time, I was bitten by the bug, (again, not the ant), and more poems began to arrive. The theme of an ant on a persons hat soon took over my life and all of my creative output, until such a time arrived that I could think of little else. Indeed, the poems began to resemble a Groundhog Day syndrome, the same repeated themes, the same story with different outcomes, different languages and tones, until within a month I had thirty such poems.

The good people at Mardy Shark publishing soon recognised their worth and a pamphlet was soon produced, titled, simply, Ant.

Ant stands as the zenith of my creativity, a full flow measure of poetic and literary sensibility, all inspired by the horror and the bizarre situation of having an ant crawl on ones hat.

You can download the Kindle version of Ant herehttps://www.amazon.co.uk/Ant-Robert-Garnham-ebook/dp/B071JDZJ7X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1497201234&sr=8-1&keywords=Robert+Garnham+Ant

Or you can send off for the physical version here http://www.lulu.com/shop/robert-garnham/ant/paperback/product-23218401.html

Life lessons from performing spoken word

Life lessons from performing spoken word

1. If at first you don’t succeed, act as if you’ve never failed.

2. Image is everything. If you arrive straight from work wearing a shirt and tie, then this will become your look and people will always see you as a performer who wears shirt and a tie.

3. If a poem isn’t working, give it a third verse freak-out. Then take out the first two verses.

4. Watch out for light fittings when using props.

5. The audience wants you to do well and will be on your side but try not to balls it up in the first place.

6. The whole world is an audience even if you’re not performing.

7. You never stop performing, even when you’re not performing.

8. If you need to ask the host if you’ve got time for ‘one more poem, a short one’, it means you haven’t rehearsed. In any case the host will always say yes, because they’re just being polite.

9. When you’re rehearsing, stand at the bottom of your bed and rehearse to the pillows. They will stare back kind of blankly.

10. Like sex, there’s no wrong way of doing it.

11. Like sex, you can get a lot of laughter from just one look.

12. Everyone has a voice. Authenticity is everything. Every stage character is just an exaggerated version of yourself.

13. If humour’s your thing, the obvious joke can often be the most effective. Sadly.

14. If it’s a high concept poem which needs a lot of explanation, then it’s probably not going to work very well. But don’t stop experimenting.

15. Music stands to hold your book allow you to make extravagant hand gestures if you haven’t learned the poem by heart.

16. It doesn’t matter if you haven’t learned the poem by heart. Just make sure you don’t hide behind a huuuuuuge folder.

17. You can imagine the audience naked if that helps, but the audience might be imagining you naked too. In fact they probably are. How else to explain the amazing amount of people who upchuck during my gigs?

18. Everything becomes subject material for your poetry. Emotional turmoil, break-ups, losing your car keys. The last time I had a break up I thought, oh good, I’m going to get some poems out of this.

19. It was going to happen eventually, the bastard.

20. By all means copy the mannerisms and style of your heroes, but for goodness sake, innovate.

21. I mean I thought it was going ok but then one day I suddenly thought, hmmm, we’re just going through the motions.

22. Spoken word artists get their points across, they draw attention to injustice and prejudice, they make you laugh, they make you cry. They play with language and dance on grammar, they play with rhythm and rhyme. It’s always sickening when this is all done by one genius youthful bright-eyed performer. I remember the Bristol Poetry Slam. I was up against someone performing an excellent poem about the death of their grandmother linked in with the entire history of the British black experience from slavery to the present day, and then I went up and did a poem about liking beards.

23. Don’t worry about anything.

24. Just a small planet in deep dark space and our time on it is incredibly small in the general scheme of things, everything is relative.

25. You can take the mic off the stand if you like, but move the stand out the way. Take down that barrier!

26. If you enjoy it and have fun, then so does the audience. And so does everyone. Even the people you see on the bus on the way home. Enjoy it. The world becomes a better place.

27. There’s no subtle way to plug a book.

28. My book is available here. https://burningeyebooks.wordpress.com/2015/11/19/new-nice-by-robert-garnham/

Six poems inspired by tea towels.

One of he weirdest projects I had last year was to write thirty one poems about tea towels. Here are six of them, all inspired by the pictures on my mothers tea towels. Hope you like them.

Poem

1. How would you describe the behaviour of cows?

Cows line astern

Grass munchers in a row

Like forensic detectives

At the scene of a crime.

2. Are you familiar with bovine behaviour? Y/N

N

3. Describe the types of cow that you saw.

Fresians black and white

Flanked by invisible maps.

Half of an hour hyped up.

Are they black cows with white splodges

Or white cows with black splodges?

4. Have you ever been caught under the silvery moon suddenly transfixed by the inate beauty of cows and the way that they seem to reflect the celestial moonglow as if lunar objects themselves?

N

WTF?

5. Were you aware of this before the incident?

I had a crush.

6. Explain in a single haiku the beauty of the cows you saw.

There once was a field of cows

Upon which I would browse

By the side of the gate

And other places on the farm

Often in shady areas but sometimes in the full glare of the sun.

7. That’s not a haiku.

Oh

8. Eulogise a cow for me.

Daisy

I know this rhyme is lazy

And people may think me crazy,

Daisy

But in this rhyme I praise thee.

Says me.

Daisy

You are amazy.

9. Tell a cow joke.

In what way is a cow like my parents bungalow?

10. I don’t know.

They’re both fresian.

11. Do you have anything else to add?

I have no beef with you.

12. So I herd.

Poem

The quivering chrysanthemums

Which, in their stately manifest,

Seem to shield all harm from life,

Colouring the inevitable with an

Affected glee multiplied by the

Verdant nature of their bloom,

Would justly fill my jaded heart with

Inordinate bliss, but until such a time

That I may bask in their chrysanthemummy goodness, I must

Temporarily satisfy my whims with

Hydrangeas and the occasional

Rhododendron.

Poem

On the fifth night we argued.

Lightning illuminated my lonely garret,

Flickering omens of someone else’s storm,

Grouching and crackling the radio with static

As I tried to find French soap operas,

Lazy drops falling from an overcast night sky,

Stained brown by sodium lights,

Rolling ever so sadly down sash window panes.

You fumed.

I stare out the window at a jumble

Of slate tile rooftops sheening in the rain.

Momentary sheet lightning illuminates

Jagged architecture, chimneys, television aerials,

Your sour face.

There is no such thing as perfection, you said,

In your defense admittedly,

Having skewered my heart with mild

Grumbling a which seemed to match the

Rumbling thunder.

Having supplied a list of all

The things in which I fail.

And now you say, there is no such thing

As perfection.

Yet I read your blog, in which, in

Glowing terms, you eulogized and praised

And refused to criticize the herbaceous borders

At Polesden Lacey.

Poem

He set up a library in which people borrowed not books

But tea towels.

And they were classified dutifully under the

Dewey decimal system

According to their subject.

People said he was mad.

The two most popular sections

Were Travel, and Cats.

The Travel tea towels arranged on shelves

According to country, region, town, city,

Municipal districts, culture,

The cats tea towels

Were all kind of clumped together

Although some attempt had been made

Discriminating long hair and short hair.

Plain tea towels were measured

As to their viscosity and were

Stored in their sections,

Friction and non friction.

On most days he would appear

From his office in a 1920s showman’s outfit

Complete with top hat, jacket and bandsman’s trousers,

All made out of tea towels,

And he would dance along the aisles

As if caught up with the absolute romance of

So many tea towels.

People said he was weird.

The humour section was off limits to kids.

One of the tea towels was a bit saucy.

Some people don’t wash them properly.

Poem

An early morning sun

Sets afire the desert land.

An opal mine shimmers on a heat haze.

Nothing but sand

And the dull empty crack of life,

Existence as grand.

In a tin shack bar sits Jack,

Fresh from the dust, weary from a

Fortnight’s driving, weary, he caresses

A cool early morning beer.

How many sheep will he have to sheer

Until his dreams come true?

Yesterday, he dreamed of rodeos.

This morning, the outback sky was split

By a lone vapor trail, at the head of which,

An aircraft reflected the morning rays

Heading south to cooler climes.

We live in fantastic times.

Seven AM, already thirty degrees.

He ponders on unseen passengers,

Heading to their cool bars, their

Cool night clubs, their cool trendy flats,

With their cool friends, their cool husbands

And their cool wives, watching the latest cool

Films and reading the latest cool novels,

How cool it must be to be so cool,

Oh, right now how he wishes he were cool!

He traces his forefinger on the frosted glass

And ponders on appetites, fashions,

A suburban existence,

And the thought that a landscape so vast

Could easily suffocate a weaker soul.

The tin shack radio blares through static

Seventies rock opera, and in the distance

He can hear the chug chug from the opal mine

And the bleating of sheep.

Poem

You said you loved me

And you’d get a tattoo of my face to prove it.

Only when I peeled back your sleeve

Expecting to see my own youthful twenty-something visage

Emblazoned in ink on your upper arm

I saw instead a depiction of

The secret lost garden of Heligan.

I was most indignant.

You said you’d had a sudden change of heart

I pointed out that the

Secret lost garden of Heligan

Was neither secret nor lost

Because they’ve got a website

And a Facebook page

And a Twitter account

And several published coffee table style books.

You said that tattoos are permanent

And the nature of gardens in all their seasonal

Glory are but momentary depending on the whims

Of the climatic variables which make up this

Fine isle, they never look the same

One day from the next

And I said, neither do I.

I began to have my suspicions

That something was amiss

When I saw a little old lady at

The garden centre coffee shop

Who had a tattoo

Which was a very fine outline of my own

Facial features

And I said to Dean,

Was there a mix up at the tattoo parlour?

Yes, he said, there had been

A hideous mistake

But the old lady thought that her new tattoo

Was of snooker player John Parrot

So she was quite happy.

(His name was Dean,

I should have mentioned that

Earlier in the poem).