Are you Cool? Performed live in Edinburgh

Performance poet and Professor of Whimsy

Had a great time last night performing at Screech Night at Banshee Labyrinth.

Here’s a poem about glamping. It’s one of those expressions I hate, along with ‘side hustle’.

1.

'Let's just slink through here', I suggested, gesturing to the rhododendrons.

A hot tropical night. The sweat was pouring down my face. Out to sea there was thunder, lightning flashing, but here on the beach, fairy lights and candles threw multicoloured light and shadows which danced.

'Slink?', Jack asked.

The scent of jasmine and honeysuckle hung in the Caribbean night. The sky was dark and starless.

'There's a storm coming'.

'It's just . . The choice of word'.

Others on the beach were standing at the water's edge, looking out at the storm. It was obviously getting closer.

'Are we just going to stand her end argue about a word?'

'It's better than arguing about whether we should argue about a word, which is even more pointless than arguing about a word'.

'OK, let's just ignore that and shimmy into the rhododendrons'.

'Shimmy?'

'Oh, for heaven's sake!'

There was a rumble of thunder, and fat lazy drops of rain began to fall from the sky. They thudded into the sand as perfect darkened circles like sudden coins.

We penetrated the outer fringes of the rhododendron and found ourselves surrounded by branches cross-crossing, and roots, and a sandy, springy earth. We could hear the rain falling on to the fleshy, heavy leaves around us, as if the world were applauding our efforts. It was cooler within the foliage.

'This might not be the time to tell you', Jack said, 'But I'm a member of the RSPCR'.

'What's that?', I asked, ducking to avoid a low branch across the face.

'The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Rhododendrons'.

'Bloody hell, what are the chances?'

'We also cover hydrangeas and certain types of buddleia'.

'Well, we're not exactly being cruel, are we?'

'The constitution has several definitions . . .'.

'You're making this up!'

'I might be'.

But he had a point. I hardly knew him. We'd met at the backpackers hostel the night before. He'd let me use his spork.

'There will be spiders in here'.

'GAH!'

'And snakes, probably'.

I'd not thought about either of these scenarios. Thunder boomed and the whole earth shook. Neither of us said anything for a while, and then, of a sudden, we entered into a tiny clearing surrounded in all four sides by rhododendron bushes and tall palm trees, sheet lightning behind the overcast swirling clouds.

I took a step, and spluttered, wiping a spiders web from my face. He emerged behind me and we stood there, feeling the heavy drops of rain on our shoulders.

'Amazing', he whispered.

And then the storm begun in earnest, ripping the sky with vicious lightning bolts, the rain thudded down with increasing intensity, we sheltered under the dripping leaves of the vegetation, his warm body pressed close to mine as the thunder boomed and crashed and roared around us.

'Do you think', I asked, 'that this is a sign from the universe? That we should be together forever?'

Because all of a sudden, I was caught up in the sheer magic of the moment.

And at that second, a bolt of lightning hit one of the palm trees right in front of us, a vicious spew of sparks tearing off one of its branches with incredibly ferocity

'Not really', he said.

2.

Amid the midnight neon and the motorway flyovers of Tokyo, the incessant thrum of feet on the busy pavements, the night itself an electric pulse of brash branding, logos, cartoon charms and corporate magic, I found the doorway to the capsule hotel, the Paracetamol, between a gaming arcade and a brightly lit vending machine selling live koi carp. The front desk was automated and I booked in using my credit card, taking a lift up to the fifth floor, where a sign on the wall, accompanied by an over-the-top cartoon caricature of a hotel porter who also happened to be a giant panda, reminded me to be quiet, respectful to the other guests, and to take care of my own personal hygiene.

My backpack almost didn't fit in the locker provided, and then I realised that the locker that I was trying to cram it in to was actually my room for the night. A mounded plastic bunk into which had been added a television, the bed, control panels for the heating, some robes. I put on the robes and went wandering around the corridors of the Paracetamol. As well as showers, bathrooms and a row of vending machines, (instant noodles, books, lanyards, and what looked like weasels), there was a small lounge right in the very corner of the building, looking down on one of the busy intersections below in all its neon glory.

There was only one other person in the lounge. I sat down on one of the soft cushioned sofas and I looked out the plate glass window at the intensify and madness of the city. I then looked at the other person and I let out a gasp.

'Jack!'

'Yes?'

'Remember me?'

He kind of frowned.

'Paya de los Aquafresh? We hid in the rhododendrons during the thunderstorm that time!'

His face lit up.

'Yes! I remember! My god! We sheltered in the rhododendrons . . . And that lightning bolt took a branch off a tree right next to us!'

'What are you doing out here?'

'I'm in a business meeting with the RSPCRHB'.

'I thought that was a joke . .'.

'Deeply serious'.

'What are the two extra letters?'

'They've let in hydrangeas and certain types of buddleia since I last saw you'.

'I can't believe you're here!'

He got up and joined me on the sofa and sat right next to me. And it felt good, his being there. In our robes, loose fitting and comfortable, it felt almost as if we were naked. How amazing! Two souls, coming together in spite of all the odds.

'I often think about that night', I tell him.

'Really? I can't remember much about it'.

'The storm, and the rain . . . And being with you'.

He smiled. We were both speaking softly now, hushed tones in case we were to wake any of the other people staying at the Paracetamol, but the hushed tones could very well have been the purred small talk of love.

'You said slink, remember that?'

'I did'

'And then shimmy'.

'That's right'.

I was so happy. I felt like putting my arm around his shoulders.

'You see, I would have said something different. Plunge, perhaps, or even hide. Or shelter. Let's shelter in these rhododendrons. But the way you said it . .'.

'Yes?'

'It hinted at something different'.

'This is a very weird conversation'.

'Is it?'

'A conversation about a conversation, and that conversation itself was mostly about the conversation that we were having'.

'I don't see why you've had to bring this up now'.

'Well, it's not like we're going to be meeting up again, is it?'

'Why not?'

'I . . . Don't know'.

‘Do you think', I asked, 'that this is a sign from the universe? That we should be together forever?'

Because all of a sudden, once again, I was caught up in the sheer magic of the moment.

He was quiet for a couple of seconds, and maybe it's my imagination, but he kind of snuggled towards me on the sofa, his body getting ever so slightly closer to mine.

And at that moment, a sudden bolt of lightning was hurled from the overcast sky, lighting up the traffic intersection and the lounge with incredible ferocity, hitting the neon sign directly opposite from us of a cartoon duck advertising some local brand of shampoo. And before our eyes the cartoon duck sizzled, smoked and swung on its screws, turning upside down, unlit, where it pendulumed from side to side.

'Not really', he said.

3.

By my third day in the tiny Arctic community, I’d already worked out that there wasn't really much to do. The small huts, shacks and prefabricated homes sat shivering in the snowdrifts by the frozen sea, and it was dark by two in the afternoon. Once I'd visited the Museum of Permafrost and had a look around the art gallery built to resemble the tusk of a walrus, I'd more or less run out of activities.

My only solace was the town library, a quaint prefabricated structure whose tiny lit windows created elongated squares in the fallen snow. I'd found a quiet corner, in between Arabic Numerology and Paranormal Studies, where I could sit near a radiator and read the hours away.

And this is what I was doing, one never ending afternoon after dark, when I looked up and . . .oh, for heaven's sake.

'Jack?!'

'You!', he said.

And he just kind of stood there for a bit in his big Arctic survival suit, and I stood, and we faced each other across the town library.

'What are you . . .'.

'Rhododendrons ', he replied. 'The feasibility of Arctic growth'.

'And?'

'None'.

'I can't believe it's you!'

His face relaxed, and he came over and sat next to me. The tiny window between us began to be speckled by another snow shower, each fleck illuminated by the library lights.

'The last time we met . . in Tokyo . . Do you remember?'

'Yes'.

'We had a conversation about having a conversation about the conversation we'd had in Paya de los Aquafresh, in which the conversation had been about the conversation'.

'And now we're having a conversation about those conversations'.

'Yes', I laughed, 'we so tend to have a lot of conversations'.

'No fear of any lightning today', he said, 'though it's just started snowing again'.

'It's so good to see you'.

'You too'.

'Thanks for letting me use your spork'.

'Yeah, no problem'.

And then the conversation kind of ran out of steam for a while, and we just sat there, listening to the sound of water in the heating system, the crunched footsteps of people walking in the snow.

It was good to see him. The padded layers of his Arctic survival suit gave him a sudden cuddly physicality. I could hardly believe that he was there, that e we're together yet again, but it had happened twice before and yet again I could feel the planet turning, the magic of existence itself funnelling down, very much like the aurora borealis itself, and this isolated community. I looked past him, to the reception area of the library where Librarians were busying themselves, and a poster warned of the drawbacks of trying to pet a polar bear. The same old question seemed to press itself up from deep within me, into my vocal chords before it got a chance to be processed by my brain.

‘Jack’, I said.

He gulped.

‘Do you think . . .’.

‘I'll have to stop you right there’, he said.

The two of us smile at each other. In the pallid fluorescent glow of the Arctic community library, he looked serene, playful. I could hear someone moving bins outside and it sounded like thunder, but it wasn't.

‘I think I'll saunter out in a bit’, I say to him, ‘and see if I can get any dinner’.

‘Saunter?’

‘Yes? What's wrong with that?’

‘Nothing, it's just . . A very strange word’.

‘What should I have said? Mooch? Jimmy?’

‘I don't know, it's just . . .I mean, of all the words you could have chosen . .’

The snow was coming down increasingly heavy now and piling up on the little windowsill.

‘I'll come with you, though’, he said, after a short while.

Here’s a video of my poem ‘Sofa Phobia’, filmed earlier this month in Penzance. It’s true, I do have a phobia of sofas. They’re disgusting things. It’s nice that I can laugh about these things.

This is an old poem, one of the first I ever performed. And I’m still performing it after 15 years!

It’s not very long.

Oh, when the goose is amorous,

Willing to express his tender romantic inclinations

To Mrs Goose

And love is quite the possibility,

Goose poetry forms in his mind,

And words take on extra meaning

To which he gives voice,

To goose sonnets and goose odes

To explain his heartfelt love.

He takes a deep breath

And strikes her gentle shoulder

And says

HONK

A storm of words cascades through his brain!

He eulogises the sweetness inherent in Mrs Goose

That she should set afire his soul

With burning lust,

That he should softly purr this tender refrain:

HONK

And Mrs Goose is turned on by his words,

Turned on by the subtlety of his eloquence

And replied with great charm

And a keen eye for erotic repartee

HONK

William Shakesgoose with his feathery quill

Penned odes to love which on the page he did spill

Explaining what it mean to be alive and be free

That even today we should proudly quote he

Standing proud on that Elizabethan stage and proclaiming

HONK

Oscar Wildgoose, with a fey wave of his wing

Could reduce a room to laugher with his legendary wit

For language danced at his beck and call,

Such hilarious put downs and Bonne mots

For he was often heard to quip:

HONK

Flying to Belgium

The pilot just happened to be a goose

Came over the tannoy to give us

The expected arrival time in Brussels

HONK

A crowd of sexed up male gooses

Gathered outside the vehicle hooter testing facility

They’re getting ever so wound up

By the sky sexuality of the

Noises coming from within.

Oh, baby baby,

Talk dirty to me.

HONK

Goose literature

Translated for a feathery audience

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

HONK

Les Miserables

HONK

The Canterbury Tales

HONK

Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu

HONK HONK

(It’s in two volumes)

And perhaps

A haiku

HONK

The man of my dreams, so butch and fit

With a face like Adonis and the body of a god

Oh, I said to him, sing for me, Stefan,

Give voice to your

Rampant masculinity

And he said

.

.

.

.

HONK

In 1992 I was 18 years old and wanted ever so desperately to be a writer. I was inspired by anyone who could make me laugh. Douglas Adams and Clive James were both very important in my writing aspirations.

I’d been writing the Bill Board books since 1985, (see my previous blog,https://professorofwhimsy.com/2025/06/18/my-writing-career-part-2-the-bill-years-1985-2022/). In 1992 I was studying, or I should say, ‘studying’, for my A Levels at Strode’s’ College in Egham, Surrey, and the idea came to set the next Bill Board book there.

It was incredibly fun to write and I enlisted the help of various friends and classmates. My friend Damian designed the cover, and I included quotes from various friends throughout the novel.

The story was very slim. Bill and Justin go undercover at a sixth form college to stop criminal activity. The plot was just secondary to the endless jokes and wordplay, a lot of which, looking back, weren’t very clever at all.

So here are some of the pages of that pivotal work!

(This follows on from the previous blog)https://professorofwhimsy.com/2025/06/15/my-writing-career-part-one-1980-1985-age-6-11/

At ten years old, I did feel somewhat held back, and I worried that my stories about secret agent dogs were getting a bit old hat. In late 1985 I must have been given another exercise book, because before I knew it, I’d started a brand new story which was innovative on a number of different levels. The first level was that the lead character was not a secret agent. He was a skier, who competed in the skiing world championships and the Winter Olympics. The other level was that he was a human being. And his name was Bill Board.

Now, looking at the title of that first book causes a shudder of embarrassment. Yet I can at least comfort myself that I did not come up with the title. You see, the story begins with a skier by the name of Clive, who comes up with the idea that he get a head start at the beginning of every ski race by having his friend, Bill, give him a hefty push. One day Bill pushes too hard, Clive falls over, and Bill goes off down the mountain on his own. Indeed, so well does Bill do, inevitably winning the race, that he is invited to participate in every ski race thereafter. So, representing the UK, Bill becomes, by the last chapter, the skiing world champion. And the title? ‘Nobody Can Fold Up the Union Jack’.

At the time, I thought this a rather clever title. My friend Mark had suggested it, because Bill won his skiing races so often that the organiser had to keep the Union Jack out so that they could raise it on the winner’s rostrum. But soon afterwards I became aware of the patriotic overtones, which I found, even at the time, somewhat silly. I don’t know why I was intelligent enough to realise that the title was overtly and perhaps stupidly patriotic, and yet not intelligent enough to realise that I could simply change the title.

By now I was 12 years old and I wanted, oh, how I so desperately wanted to be a writer. I was obsessed with writing, and it was probably all I ever did. Once Nobody Can Fold Up the Union Jack was finished, I launched into several more Bill Board stories. And some old habits began to creep in. Bill and his friend Clive, having won the skiiing championships, were then asked to become - oh dear - secret agents. Over the course of 1986 and 1987 I churned out fourteen of these buggers.

I remember family holidays in which we’d all stay in a caravan somewhere like Bognor or Hastings, and I’d be writing away whenever I had the spare time. I vividly recall a summer evening in Hastings, walking along a hedge-lined country lane after dinner, riding a funicular railway down to the town where I bought an exercise book, the opening paragraph of the next Bill Board story winding its way through my head. We played crazy golf and walked along the beach, but I couldn’t wait to get back to the caravan. Once we’d taken the funicular back up to the site, I remember sitting at the caravan table, opening the exercise book, and writing into the night.

By now I was at secondary school. You’d think I’d have to put all of my energy into my studies, but alas, the Bill Board stories came thick and fast. My English teacher, Mr Smith, was encouraging, and took a few of them home to read, and it’s a wonder that he didn’t then decide to retire right on the spot. He did correct some of the spelling, bless him. I remember that Christmas sending him a Christmas card and saying to my mother that he’d probably mark it out of ten and send it back.

In 1988, I realised that I’d slowed down the Bill Board output. As a remedy,I bought an exercise book and worked on one final story, which was called ‘Robot on the Rampage’. A couple of things changed in this book: Bill’s friend Clive moved away. A lesser character, Ed, and Ed’s wife Lenda, kind of took Clive’s place. Bill was desperately trying to vanquish a rogue robot while at the same time take part in what he knew would be his last ever Winter Olympics. Things were changing, not only for Bill, but also for me.

The big thing that had changed was that my Grandparents had given me a typewriter. It was a huge old Olivetti, the kind that wouldn’t look out of place in an old black and white film of a newspaper office. And oh, how I loved that typewriter! I nicknamed it ‘The Tripewriter’, and wow, I really had to bang down on those keys to get the feint ribbon to make any kind of mark on the page. It must have been insufferable for my parents and our neighbours in the estate, what with those thin walls, to hear this typewriter banging away all afternoon. I ended up using it in the garage, knowing that this would keep some of the noise pollution down, not knowing that our neighbours were running an illegal mini cab company from their caravan and the racket from my typewriter was interfering with their antiquated radio system.

I’d grown up, and I’d decided that my stories should grow up too, now that I had a proper typewriter. My parents gave me a wad of yellow typing paper and I started work on a story called The Ghost of Professor Burton, a ghost story set in the fictional village of Englemede. It felt weird writing some that that didn’t have Bill Board as the lead character. In my mind, he was now safely retired from both skiing and being a secret agent, thus allowing me the serenity to work with other characters.

The Ghost of Professor Burton was a minor achievement. I asked my sister to draw a front cover for it, and then launched into another ‘book’ based in the fictional village of Englemede. But I missed Bill. Oh, how I missed Bill.

Once the second Englemede story was done, I knew that I would easily lose interest in writing unless I did something drastic. And that drastic thing was to bring back Bill Board. Only this time, things were different for Bill, too. The third Englemede story begins with Bill moving to the suburban village and, rather inexplicably, being hired to be the village policeman. His first job is to investigate a shady businessman who wants to build a theme park on the outskirts of the village, and this book, Scheme Park, (and oh, how I loved that title), was probably one of the most important things I’d write. By keeping a character I knew well but changing all of his circumstances at a time when everything was also changing for me, it felt, with hindsight, that Bill was also along for the ride, and that he’d never actually left me. Sure, Clive had moved away. And sure, now he had moved away from Ed and Lenda, but now he was in a new town, with a new job, and a new purpose. And I was on the cusp of my GCSEs and I had discovered that I rather liked men.

I was very happy with Scheme Park. Happier still when a classmate called Kevin actually made an electronic Kraftwerk-inspired rap-infused song with Bill as the subject matter. The chorus went, ‘Bill Board, Bill Board, B-b-b-b-ba-Bill Board’, followed by, ‘Englemede, Englemede, Eng-eng-ah-Engle Englemede’. Kevin was a genius before his time.

In 1989, I decided that what the Englemede stories needed was more Bill Board. But I was a veritable writing machine. Not satisfied with Englemede, I also wrote Ed and Lenda books, done the old fashioned way in exercise books, detailing their lives running a seaside bed and breakfast, and for some reason, a second hand book shop while getting into the usual japes, scrapes and highjinks. These were of lesser importance, as I was rationing my typewriter ribbon and typing paper for other projects. (Incidentally, I still have The Tripewriter even now and I often use it when I'm a poet in residence at various corporate events).

The next Bill Board / Englemede story introduced a new assistant for Bill, in the shape of Justin. Justin was a by-the-rules stick-in-the-mud, and also, in my mind, significantly younger than Bill. In fact, to be honest, I see Justin as representing myself, whereas Bill was more the Bob Newhart kind of character who surrounds himself with eccentric types and bizarre storylines. And once this new partnership of Bill and Justin was established, I also introduced Bill’s girlfriend Polly, (artist and daughter of an inventor who lived in Scilly Isles, because, why not?), and his bosses Sue and James.

So by the end of 1989 I had a lot going on with school work, an infatuation with various classmates, the usual throbbing hormones of any 15 year old, a weird interest in American stand-up comedy from the 1950s, and the pop music of the Pet Shop Boys. Things needed simplifying, and this is when I came on the novel idea of ditching the Englemede stories, the Ed and Lenda stories, and combining them all as The Defective Detective Casebook.

By this time I’d also started reading other humorous writers. It didn’t matter who they were, so long as they made me laugh. Not only obvious choices like Douglas Adams and PG Wodehouse, but also anything else which used humour primarily, such as the Heroic Book of Failures, the Garfield cartoon strips, and of course, anything by Bob Newhart. As a result, the tone of my writing shifted towards an impulse to crack a joke in almost every sentence. And while this felt great at the time, the results are, sadly, quite unreadable. And in the midst of this maelstrom of gags and meta-fictional narrators who would address the reader personally and say things like, ‘Look what happens in this next sentence’, was Bill Board. Reading my work from this period now can be quite exhausting.

It was around this time that my parents bought me an electric typewriter. And to be honest, I don’t blame them. They were probably fed up of the house being shaken to bits by the clunk and crash of my old Tripewriter, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the plaster wasn’t falling from the ceiling below my bedroom. But that electric typewriter was a godsend, and it meant that the typing process certainly wasn’t as strenuous as it had been with my old Olivetti. Indeed, for the first few months I would press the keyboard of this new electronic typewriter much more heavily than I actually had to because I wasn’t used to using a machine with such a light touch. Indeed, even today typing these very words, I have to make a conscious effort not to hit certain buttons heavier than others, because I have been so conditioned that certain letters stick. Like Z or X. It’s such a novelty to write words like zebra or xylophone without having to stop everything and prize the hammer away from the page.

So by 1990, Bill, Ed, Justin, Lenda and Polly had been consolidated into the Defective Detective series. This made everything much easier. Ed and Lenda still lived at the seaside, but it seemed that every storyline had some reason for Bill and Justin to have to go down to the coast to solve a crime. Or perhaps Ed and Lenda might come back and visit Bill and Polly, and help with whatever case they were working on. Everything seemed right with the world.

Also by 1990, I’d moved to sixth form college. And now I was studying for my A-Levels. I was never the world’s greatest student, and it is only recently that I’ve discovered that I’m one of the many people who have dyslexia, which certainly would have made things more difficult when it came to comprehending the higher levels and concepts of A-Level syllabuses. So the fact that I started churning out even more Defective Detective novels really was taking my attention away from my studies.

The first Defective Detectives novel was just called Defective Detectives. The second, (and, oh dear, I’d discovered surrealism at this time), was called The Final Revenge of the Boring Spud. The third was called A Healthy Alternative to Suicide. These novels became fairly formulaic, with Bill and Justin tasked by their bosses, Sue and James, to go and investigate some robbery or kidnapping, only to discover that their arch nemesis, Count Ivan Von Wurstfrech, was behind everything. A trip down to the coast would follow, and invariably, a car chase or two, until Count Ivan was stopped in whatever mad scheme he had undertaken. Yet the storyline really served a secondary purpose to various one-liners, jokes and bits of silly wordplay which were probably far more fun to write than to actually read.

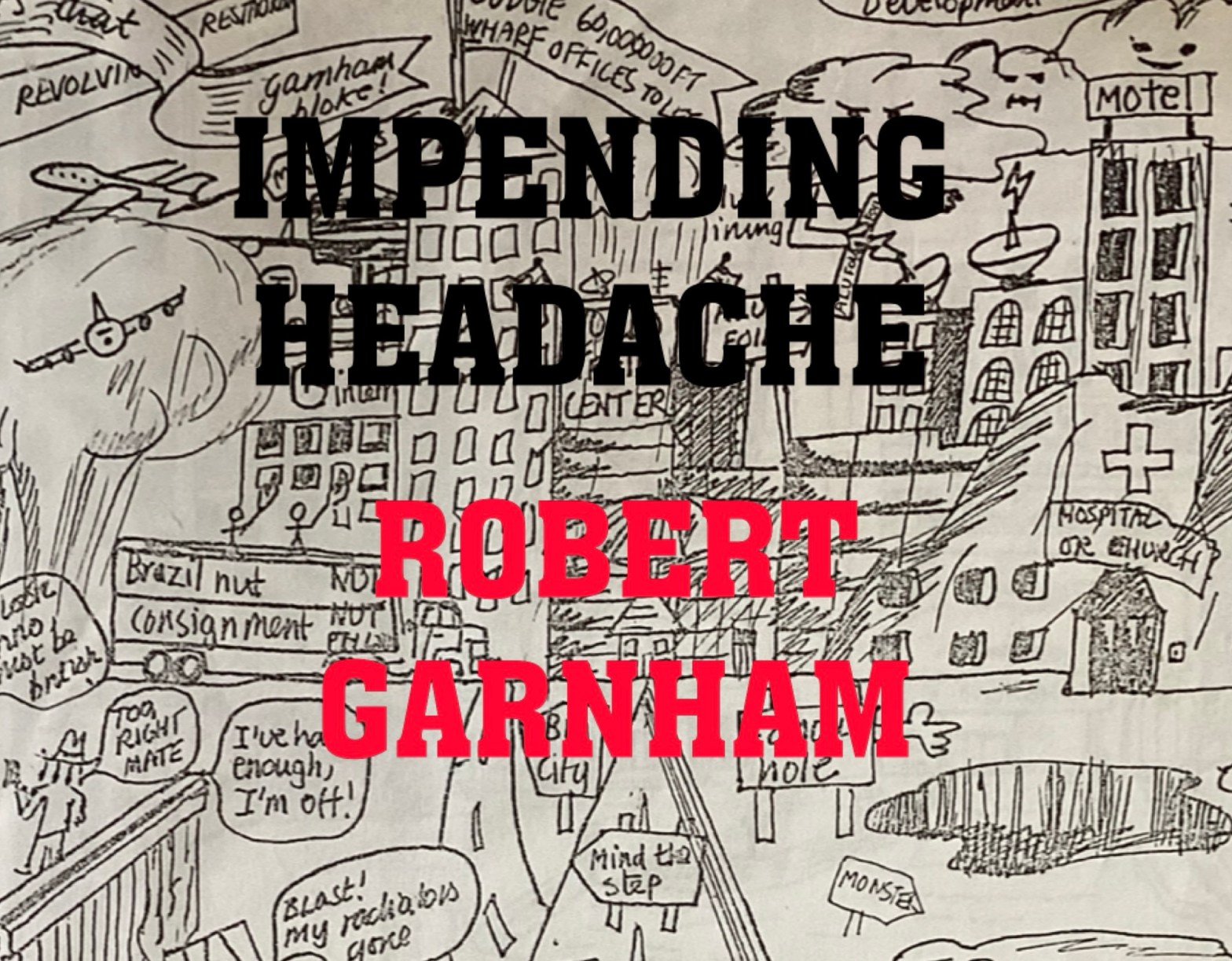

Take this first paragraph of 1991’s Impending Headache:

Things never seem as bad as they are when seen from a different angle. But then again, things seem worse when they are viewed before they have occurred or if viewed from yet another angle, but things may turn out as expected if expected, but sometimes, if you expect something to happen, it doesn’t happen at all or happens but not as expected. This will cause the expector or expectee to look back upon what had happened and decide whether or not it was better or worse than expected, I expect. Unless he’s dead because of what happened. Or she. Can’t be sexist.

Impending Headache was one of the highlights of the Defective Detectives saga. Indeed, it was my most ambitious piece yet, set at the sixth form college where I was studying and featuring thinly disguised version of my friends and teachers. Bill and Justin went undercover to infiltrate the college, where Count Ivan was up to his usual tricks, and in the process one became a teacher, the other a student. The storyline was the usual faff, but the process of writing Impending Headache was one of the most fun of the whole series.

I involved all of my classmates and got them to donate sentences, which became enmeshed in the actual narrative. My best friend Damian helped design a totally bonkers front cover which showed the college and most of the teachers as cartoon characters. At the bottom of each page were totally unrelated cartoon featuring a set of cartoon characters we’d devised, Geoff and his friend Mr Woollytarnish. In between each chapter were hidden extras which had absolutely nothing to do with the plot. The book ended with this legal warning:

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without first slipping the author a fiver. All major credit cards accepted.

The thing is, I put so much work and effort into Impending Headache, and absolutely none into my A-levels. Consequently, my grades weren’t good enough for university, and in the summer of 1992, I started my first ever job at the local branch of Sainsbury’s.

1992’s first effort was called The Blue Chicken, which seemed a bit mundane after Impending Headache. Bill and Justin were tracking the evil Count Ivan and for some reason he’d ended up at the seaside town where Ed and Lenda had their book shop and guest house. By now, I would say that writing was definitely more of a therapy and an assertion of who I was as a human being. Still closeted, living in a world that was still largely homophobic, too afraid to find love as this was also the height of the AIDS crisis, and now separated from all my friends who had gone off to university, the only thing I could do, apart from cleaning the aisles, storerooms and toilets of the local supermarket, was write. And naturally, I fell in love, and had a brief friendship with someone which didn’t go anywhere much, so coming home every night and writing until about two in the morning seemed the perfect way to take myself away from the world.

The Blue Chicken was followed very quickly by Bar Code Blues. This was probably the second best of the Defective Detective books. Kind of following the success of Impending Headache, this time Bill and Justin were sent undercover to the supermarket where I worked, where, surprise surprise, the evil Count Ivan was up to his ghastly schemes. Again, the actual storyline was thin to say the least, but the fun I put into presenting my new work colleagues as barely disguised characters was probably also deeply therapeutic.

At around this time, some people in the office at the supermarket started a very short-lived newsletter and I answered a call-out for stories they could use for their monthly circular. And thus, the first half chapter of Bar Code Blues was printed and distributed around the staff rooms of the supermarket. This was the first thing I had ever had printed, and I would sweep the floors of the produce department and dream of the big time, of being a famous writer who got his first break with the staff newsletter of the local supermarket. It was probably read by as many as ten, fifteen people.

In truth, at this time, I was probably quite a sad individual. In 1993 I decided to spend some of my wages on my first ever holiday alone. For some reason I chose the town of Looe in Cornwall, and on a Saturday morning I took the train from Reading down to the west country, and I booked into a bed and breakfast. I was 19 years old, and this felt like a big step for me. This would actually be the start of a life spent visiting towns, cities and countries and travelling to some wonderful places around the world, but this was the first time I had ever gone anywhere long distance on my own.

And what did I do while I was in Cornwall that week? I started another Bill Board novel.

By now I was running out of titles. And secondly, I thought, what’s the point? I don’t even have an audience any more. No more college friends to read the Bill Board stories, and the supermarket newsletter had disappeared after the second edition. And anyway, I thought, what’s the point of titles? I called the next novel 935, because it was the fifth thing I’d worked on in 1993.

In the narrative, Bill and Justin had been sent down to Cornwall. The evil Count Ivan was doing something illegal which involved smuggling and the Isles of Scilly, where Polly’s family lived. And that’s about as far as the plot went. However, I did have fun working on the cover for 935 on Polperro beach, spelling out the numbers 9 3 5 in seaweed when the tide went out, and photographing it from several angles. As I say, I was 19 at the time.

Three more Bill Board books followed. Last Resort Jack Chopsticks ended 1993 with something of a fizzle, and then in 1994 came A Date with Density, (I wasn’t too bad at titles after all), and then Some Stuff that Happened. (OK, maybe I wasn’t that good with titles). A Date with Density showed Sue and James being fired for incompetence and replaced, so that Bill and Justin had new bosses who they had to impress, but then their new bosses were also fired for incompetence and Sue and James came back. And Some Stuff that Happened kind of ended limply, with Bill, Ed, Polly, Lenda and Justin having Christmas dinner together. You could tell that I’d grown weary of the whole enterprise by this time, as the front cover was drawn in black biro in about three minutes, and the whole novel amounted to a massive thirty something pages.

By now I was twenty. My life was a series of underwhelming events. I was still a couple of years away from my first relationship, and I had failed at A-Levels and had a highly prestigious job cleaning toilets. Which I know isn’t a bad thing, but when your friends are all off at university and having the times of their lives, it did kind of make me question several aspects of my life.

I wanted to be a writer. Oh, how I ached to be a writer. Yet the Bill Board stories, even I had to admit, were virtually unreadable. One night in late 1994 I bit the bullet and decided that I had to write something - well, something well. And that meant no more Bill Board.

By this time I’d made the mistake of discovering existentialism. Whereas before I was reading Douglas Adams, and reading for enjoyment, I was now reading for intellectual curiosity, and because I wanted to be feted as a serious writer. I turned my back on Bill and dived further into the world of existentialism, and as a result, probably further up my own backside. I started wearing black. I went into a shop and tried on a beret. I became the most boring twenty year old in existence. And I knew that one thing I had to do without was humour. If I was ever to be taken as a serious writer, then there couldn’t be any humour.

Indeed, the humour only came back in - wait for it - 2009 when I discovered performance poetry, but that’s another story.

So for an astonishing 28 years, I didn’t even touch the Bill Board books. I became a performance poet. I spent most of my twenties and thirties having lots of sex. I studied A-Levels, university and post grad university at night school. I moved to Devon. I travelled the world. And all the time, the Bill Board books remained as a kind of memory, as if a TV show I used to watch, the plots of which I could no longer recall, just the characters and the fun I used to have writing them, banging them out on my old Tripewriter.

Also, I wonder if there was something deeper going on. At the time I was writing the Bill Board stories, I knew I was gay, but this was never mentioned not once in the text. Bill, Ed, Justin, Clive and James were all straight, in my imagination. (Though I have my doubts about Justin). Bill, Ed and Clive all had girlfriends or got married. The courtship of Bill and Polly is a major part of the later novels, though they never actually got married. It’s almost as if I had created a world where everyone was achingly straight and I, as their omniscient narrator, was therefore straight by association.

In late 2021, I decided to start work on a new novel. And for some reason, I thought of Bill, and I wondered what he might have done during the last 28 years, and what he might now be up to. I decided that he would probably have left the police force by now. At the same time, I went to visit a friend and he was telling me the troubles he was having in getting a new recycling bin delivered. Indeed, he delivered this wonderful monologue which I told him should be the basis of an Edinburgh fringe show. And then when I got home that night, I kind of put this idea together with the idea of exploring what Bill might now be up to, and the narrative of Bin just kind of presented itself to me.

It’s now the middle of 2022 and working on Bin has been one of the happiest projects I’ve been involved with for quite some time. On various streaming services you can now catch up with Jean-Luc Picard from Star Trek, and Obi-Wan Kenobi from Star Wars, because the trend seems to be for this kind of nostalgic comfort television, and in the same sort of way, this character who appeared in novels which only a sprinkling of college friends, one or two English teachers, and some staff of a suburban supermarket ever encountered, now has a chance, finally, to get something of a more modest appreciation.

And only now do I realise, reading this, that Bill was there for me at a very important time of my life. School, college, my first job, and the entirety of my teenage years were echoed in the stories. Bill was there for me, and now, hopefully, I’ll now be there for Bill.

1986 Nobody Can Fold Up the Union Jack

1986 The Return of Hugo First

1986 Steve Cramp and the Flying Robots

1986 Who on Mars is Bill Board?

1986 Wallies at the Winter Olympics

1986 Aravanta

1987 The Phantom Dustcart

1987 The Revenge of Dan Druff

1987 Copellia’s Second Go

1988 Robot on the Rampage

1988 (Englemede) Scheme Park

1989 Defective Detective

1989 (Englemede) The Gold Mush

1989 Defective Detective Two

1989 (Englemede) The Really Interesting Club of Englemede

1990 Defective Detective Three

1990 (Englemede) Too Boring for Real Ghosts

1990 Defective Detective Four

1991 (Englemede) Notre-Dame-de-Bellecombe

1991 Defective Detectives

1991 Defective Detectives Two : A Healthy Alternative to Suicide

1991 Impending Headache

1992 Defective Detectives Three : The Final Revenge of the Boring Spud

1993 The Blue Chicken

1993 Bar Code Blues

1993 935

1994 Last Resort Jack Chopsticks

1994 A Date with Density

1994 Some Stuff that Happened

2022 Bin