Advancements towards a more wholesome punctuation method

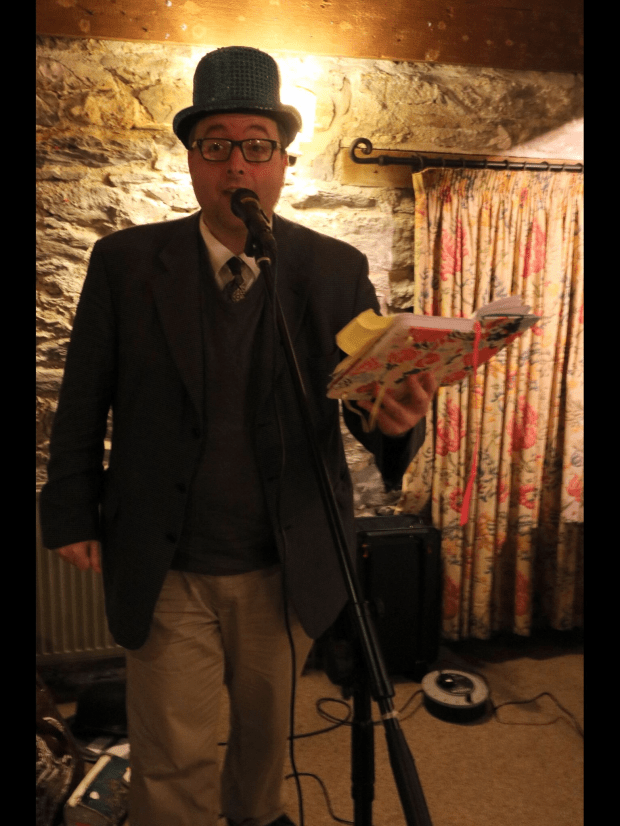

(In April 1967 Professor Zazzo Thiim published his paper on the formation of a new mark of punctuation, the ‘collard’. Initially controversial, the collard was adopted to a small degree in some institutions and in the literary magazine ‘Madam What Are You Doing With That Haddock? (MWAYDWTH)’, before being quietly rejected just a few months later. The following is a transcription of the original presentation in which Thiim’s new system was unveiled.)

Ladies and gentlemen of the faculty. My fellow scholars and students. Your highness. (Sorry, Debs, I thought you were someone else). For a while I have been concerned with the variety of punctuation and the necessity within the act of writing itself not to bore the pants off people. And while some see this as merely the responsibility of content and editorial control, in my estimation, punctuation, too, must play its part. Hello? Hello? Is this thing switched on? Imagine, if one will, that one is reading a chunk of text. Now compare this to eating a sizeable flapjack. We all know that most flapjacks are plain, especially the ones from Tesco’s, and that some have a coating of various flavours. The coating, if you like, is the subject matter. It can be sweet and it can be sour and sometimes it falls off and crumbles for no apparent reason. And you have to get the dustpan and brush out. And at my age, that’s no laughing matter.

But what of the flapjack itself? The main content, the oats and the syrup and the . . whatever the hell it is that goes in to a flapjack. These are the words. Sometimes the mixture is dense. (Madam, if you’re going to cough like that, I shall have to ask you to leave). Sometimes the mixture is dense, sometimes not so. But whatever happens, it’s hard on the old gnashers, and for this reason the occasional raisin, nut, chocolate chip or – heaven’s above! – lump of apricot, can be a pleasant and diverting surprise which does not detract from the whole flapjack eating experience, from the very flapjackness of the flapjack in question.

How can punctuation mirror this? There can be no mistake that the majority of all written text is boring and uninspiring. I’m sorry, I shall read that again. There can be no mistake that the majority of all written text is aiming for conspiring in the acquisition of knowledge, in the same way that the flapjack is aiming for the suppression of appetite, or as a healthy snack, or as some kind of weird fetish the manner of which must be best left to those who enjoy their flapjacks in private. But the eye, just the same as the tongue or the various taste glands at the back of the tongue – bear with me, I know where I’m going with this – needs its sustenance to be broken down by instances in which the mind – or in the case of the flapjack, the throat – can rest, glance away from the page, think about something else for a moment.

For this reason I have taken it upon myself to devise a system of little red Volkswagen going up a hill into the sunset – ah – sorry, I seem to have lost the next page. Now where the hell is it? I had it this morning when I was talking to that wacko from the University of Basingstoke – ah, here it is. For this reason I have taken it upon myself to device a system of punctuation in which a random symbol might be inserted willy-nilly within the text as a means for the tired mind or eye to find its bearing. Indeed, this very paragraph is filled with collards. Here’s one. And here’s another. And this line here, the one I am reading now, has several. This line doesn’t, but that’s okay because I feel rested and refreshed after the collards of the last sentence. So do you see? The act of reading has actually refreshed me.

What are the benefits of the collard, I hear you ask? The page will look exciting. Imagine, if you will, a page filled with collards. How interesting this will be! How very intriguing to the enquiring mind! How easy it will be for the eye to glance down and gauge by the application of collards exactly where one is. And perhaps we might even break down the rhythm of collards so that the mind can, on a subconscious level, pace itself until the end of the paragraph. Collards and semicollards! Quarter collards! Inverted collards! The applications are truly exciting!

And what of the corporate world? The collard has many possibilities. With no formal design or standardised font, the collard can be printed as tiny logos advertising corporate images, tiny advertisements inserted into the text. The ink industry is particularly excited over the collard’s development, anticipating quite avidly the extra ink that will be needed to print hundreds, thousands of new characters per book. I do believe that everyone will walk away from the collard experience enlightened, happy, refreshed.

And that is why, ladies and gentlemen – woh! What was that? I know you might not agree with my research but there’s no reason to throw things! And that is why, ladies and gentlemen, I have done hundreds of hours of research in laboratory conditions on Peruvian reader-monkeys, comparing the results of those who have been left uncollardised texts such as Ian Fleming and Graham Greene, and those who have before them the newly collardised versions. In every case there were reports, amid the book-chewing that one would expect, and the rampant urination common among their species, of a more placid and accepting frame of mind among those who were given the new versions. That is why, ladies and gentlemen – (I told you not to throw things!) – I am particularly excited by the collard and its many possibly applications.

Thank you for your time and patience – I said – thank you for your time and patience, scholars and students – and I’m sure that, with the collard on board, we might – Owww! That hurt. I’m down. I’m down. Medic, over here. They got me. Bloody hell, that hurt.